The Government has published its 10 Year Infrastructure Strategy covering energy. Among the tiresome hyperbole of “clean energy superpower” and games of ‘pass the blame’, although thankfully not “working people”, it recommits to the 2030 deadline for clean energy.

Electrification

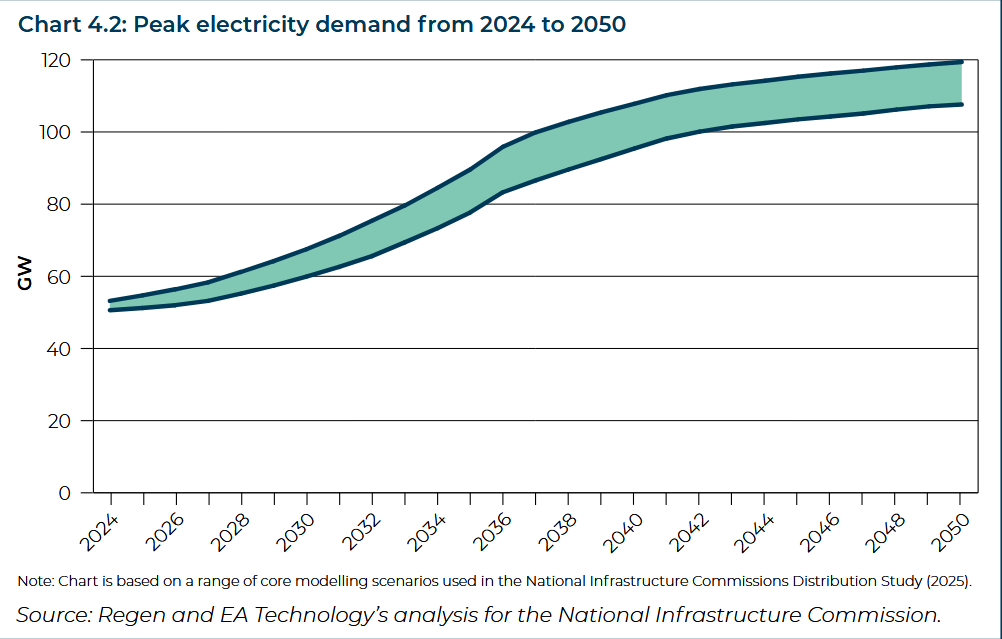

To no great surprise it identifies electrification as the primary route to decarbonisation, with electricity demand expected to at least double by 2050, and acknowledges the need for infrastructure investment, both for energy generation and networks. There is also realisation that new long duration storage system will need to be developed, but also, critically, that other methods of generation such as SMRs will be required. Based on analysis from the National Infrastructure Commission, responding to growing demand as the economy electrifies could require £37-50bn of additional investment between now and 2050.

The current electricity market was designed for the fossil fuel-based power system, so the Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA) may change the arrangements to ensure that generation resources can be used most efficiently in the future. Here, the key issue is whether to move forward with a zonal pricing model, where electricity prices vary by region, or a reformed national pricing model.

The Government has committed to conclude the policy development phase of REMA by mid-2025. In order to provide investors with sufficient confidence, projects allocated to the next auction round will be given the same legacy or transitional arrangements as existing Contract for Difference agreements, if the Government decides to implement zonal pricing.

Gas

Gas is identified as the main villain, both in terms of security and price volatility, and the document makes it clear that moving away from gas is a priority. It notes that if similar natural gas price spikes to the one which followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine occurred every decade, they could cost around 2 to 3 per cent of GDP annually. Again, though, there is a realism when it admits that gas has an important role and the Government sees support for hydrogen and CCUS as ways to provide decarbonisation options for gas and gas users. So that’s as clear as mud.

CCUS

Alongside this, carbon capture and hydrogen technologies are seen as key, as is the need to accelerate electric vehicle charge points and low carbon heating systems.

Wind and Solar

The Clean Power Action Plan, published in December 2024, set ambitions to reach 43-50GW of offshore wind, 27-29 GW of onshore wind and 45-47GW of solar projects by 2030.

Storage

The Clean Power Action Plan set an ambition for a fivefold increase in battery storage, at 23-27GW of battery storage in 2030 (compared to 4.5GW of installed capacity in 2024). It also, if somewhat vaguely, suggests that new technologies will be needed to maintain low carbon power in periods when renewable supplies are lower than demand, providing dispatchable generation across days, weeks and seasons. We’re thinking hydrogen here, but it is unclear. It notes that the National Infrastructure Commission’s second National Infrastructure Assessment set out a need for 30TWh of long duration flexible generation by 2035.

Flexibility

Consumer-led flexibility is identified as one method to manage short term fluctuations, by shifting patterns of use. some of their electricity use. The Clean Flexibility Roadmap will be published in 2025 by the Government, Ofgem and the National Energy System Operator to encourage flexibility and will contain actions across short and long duration flexibility as well as broader enabling policies such as digitalisation and markets.

Nuclear

Is identifies as a necessary part of the energy mix, both with SMRs and Hinkley Point C, that will begin generating between 2029 and 2031. SMRs are, interestingly, also fingered as having significant export potential. As are the “opportunities” in nuclear decommissioning and radioactive waste management.

Fusion remains an elusive but tantalising dream, with £2.5bn being invested in nuclear fusion including progressing with the STEP programme (Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production), the fusion plant in Nottinghamshire.

Buildings

The Warm Homes Plan, BUS and Future Homes Standard, which aims to reduce carbon emissions from new homes in England by 75-80 per cent, are seen as essential parts of the transition. What is true of the private sector is true of the public, with public buildings being upgraded, the solar schools project is an example.

Transport

The most obvious aspect is the move to EVs as the main form of motorised transport, with the ZEV mandate in place and charging points being rolled out. However the overall plan also encompasses “active travel” such as walking and cycling, and the aviation and shipping sectors where the development of sustainable aviation fuels and maritime decarbonisation.

In all the document is comprehensive, if lacking in detail, and this summary misses some of the areas such as waste and recycling, but the question remains of how the Government will be able to afford this without significant inflows of capital from the private sector.

© 2019 Perspective Publishing Privacy & Cookies

Recent Stories